The Rājatarangiṇī is a metrical chronicle of North west of

the Indian subcontinent particularly the kings of Kashmir from earliest

time written in Sanskrit by Kalhaṇa.

The Rājatarangiṇī often has been erroneously referred to as the River

of the Kings. In reality what Kalhana means by Rājatarangiṇī is Waves of

Kings. In Sanskrit Taranga means a wave. It is believed that the book

was written sometime during the 12th century. The work generally records

the heritage of Kashmir, but 120 verses of Rājatarangiṇī describe the misrule prevailing in Kashmir during the reign of King Kalash,

son of King Ananta Deva of Kashmir. Although the earlier books are

inaccurate in their chronology, they still provide an invaluable source

of information about early Kashmir and its neighbors in the north

western parts of the Indian subcontinent, and are widely referenced by

later historians and ethnographers.

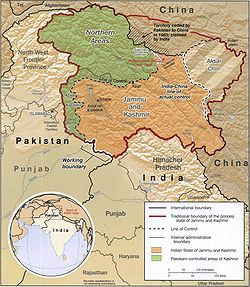

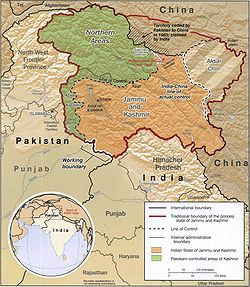

The broad valley of Kashmir, also spelled Cashmere is almost completely surrounded by the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal range.

Kalhana states that the valley of Kashmir was formerly a lake. This was drained by the great rishi or sage, Kashyapa, son of Marichi, son of Brahma, by cutting the gap in the hills at Baramulla (Varaha-mula). Vraha (in Kashmiri Boar), Mulla (in Kashmiri Molar).

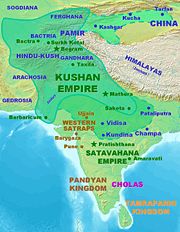

With a fertile soil and temperate climate, the valley is rich in rice, vegetables and fruits of all kinds, and famous for the quality of its wool. Kashmir has been inhabited since prehistoric times, sometimes independent but at times subjugated by invaders from Bactria, Tartary, Tibet and other mountainous regions to the North, and from the Indus valley and the Ganges valley to the South. At different times the dominant religion has been Hindu, Buddhist, Animist and (after the period of the history) Muslim.

Kalhana (कल्हण) (c. 12th century CE) a Kashmiri Brahmin was the author of Rajatarangini, and is regarded as Kashmir's first historian. In fact, his translator Aurel Stein expressed the view that his was the only true Sanskrit history. Little is known about him except from what he tells us about himself in the opening verses of his book. His father Champaka was the minister (Lord of the Gate) in Harsha of Kashmir's court.

Kalhana in his opening Taranga of Rajatarangini presents his views on how history ought to be written. From Stein's translation:

Despite these stated principles, and despite the value that historians have placed on Kalhana's work, it must be accepted that his history was far from accurate. In the first three books, there is little evidence of authenticity and serious inconsistencies. For example, Ranaditya is given a reign of 300 years. Toromanu is clearly the Huna king of that name, but his father Mihirakula is given a date 700 years earlier. It is known, however, that Mihirakula was the son of Toramana. The chronicles only start to align with other evidence by book IV,

The author of the Rajatarangini history chronicles the rulers of the valley from earliest times, from the epic period of the Mahābhārata to the reign of Sangrama Deva (c.1006 CE), before the Muslim era. The list of kings goes back to the 19th century BCE. Some of the kings and dynasties can be identified with inscriptions and the histories of the empires that periodically included the Kashmir valley, but for long periods the Rajatarangini is the only source.

The work consists of 7826 verses, which are divided into eight books called Tarangas (waves).

Kalhaṇa’s account of Kashmir begins with the legendary reign of Gonarda, who was contemporary to Yudhisthira of the Mahābhārata, but the recorded history of Kashmir, as retold by Kalhaṇa begins from the period of the Mauryas. Kalhaṇa’s account also states that the city of Srinagar was founded by the Mauryan emperor, Ashoka, and that Buddhism reached the Kashmir valley during this period. From there, Buddhism spread to several other adjoining regions including Central Asia, Tibet and China.

The kings of Kashmir described in the Rājatarangiṇī can be roughly grouped into dynasties as in the table below.

Notes in parentheses refer to a book and verse. Thus (IV.678) is Book IV verse 678.

Kalhana lived in a time of political turmoil in Kashmir, at that time a brilliant center of civilization in a sea of barbarism. Kalhana was an educated and sophisticated Brahmin, well-connected in the highest political circles. His writing is full of literary devices and allusions, concealed by his unique and elegant style. Kalhana was a poet. The Rajataringini is a Sanskrit account of the various monarchies of Kashmir, prior to the advent of Islam. Like the Shahnameh is to Persia, the Rajataringini is to Kashmir.

Rajatarangini was translated into Persian by Zain-ul-Abidin order.

There are four English translations of Rājatarangiṇī, by:

http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/discussion/Rajatarangini

Context

The broad valley of Kashmir, also spelled Cashmere is almost completely surrounded by the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal range.

Kalhana states that the valley of Kashmir was formerly a lake. This was drained by the great rishi or sage, Kashyapa, son of Marichi, son of Brahma, by cutting the gap in the hills at Baramulla (Varaha-mula). Vraha (in Kashmiri Boar), Mulla (in Kashmiri Molar).

With a fertile soil and temperate climate, the valley is rich in rice, vegetables and fruits of all kinds, and famous for the quality of its wool. Kashmir has been inhabited since prehistoric times, sometimes independent but at times subjugated by invaders from Bactria, Tartary, Tibet and other mountainous regions to the North, and from the Indus valley and the Ganges valley to the South. At different times the dominant religion has been Hindu, Buddhist, Animist and (after the period of the history) Muslim.

Kalhana: the author & his philosophy

Kalhana (कल्हण) (c. 12th century CE) a Kashmiri Brahmin was the author of Rajatarangini, and is regarded as Kashmir's first historian. In fact, his translator Aurel Stein expressed the view that his was the only true Sanskrit history. Little is known about him except from what he tells us about himself in the opening verses of his book. His father Champaka was the minister (Lord of the Gate) in Harsha of Kashmir's court.

Kalhana in his opening Taranga of Rajatarangini presents his views on how history ought to be written. From Stein's translation:

- Verse 7. Fairness: That noble-minded author is alone worthy of praise whose word, like that of a judge, keeps free from love or hatred in relating the facts of the past.

- Verse 11. Cite earlier authors: The oldest extensive works containing the royal chronicles [of Kashmir] have become fragmentary in consequence of [the appearance of] Suvrata's composition, who condensed them in order that (their substance) might be easily remembered.

- Verse 12. Suvrata's poem, though it has obtained celebrity, does not show dexterity in the exposition of the subject-matter, as it is rendered troublesome [reading] by misplaced learning.

- Verse 13. Owing to a certain want of care, there is not a single part in Ksemendra's "List of Kings" (Nrpavali) free from mistakes, though it is the work of a poet.

- Verse 14. Eleven works of former scholars containing the chronicles of the kings, I have inspected, as well as the [Purana containing the] opinions of the sage Nila.

- Verse 15. By looking at the inscriptions recording the consecretations of temples and grants by former kings, at laudatory inscriptions and at written works, the trouble arising from many errors has been overcome.

Despite these stated principles, and despite the value that historians have placed on Kalhana's work, it must be accepted that his history was far from accurate. In the first three books, there is little evidence of authenticity and serious inconsistencies. For example, Ranaditya is given a reign of 300 years. Toromanu is clearly the Huna king of that name, but his father Mihirakula is given a date 700 years earlier. It is known, however, that Mihirakula was the son of Toramana. The chronicles only start to align with other evidence by book IV,

Structure of Rajatarangini

The author of the Rajatarangini history chronicles the rulers of the valley from earliest times, from the epic period of the Mahābhārata to the reign of Sangrama Deva (c.1006 CE), before the Muslim era. The list of kings goes back to the 19th century BCE. Some of the kings and dynasties can be identified with inscriptions and the histories of the empires that periodically included the Kashmir valley, but for long periods the Rajatarangini is the only source.

The work consists of 7826 verses, which are divided into eight books called Tarangas (waves).

Kalhaṇa’s account of Kashmir begins with the legendary reign of Gonarda, who was contemporary to Yudhisthira of the Mahābhārata, but the recorded history of Kashmir, as retold by Kalhaṇa begins from the period of the Mauryas. Kalhaṇa’s account also states that the city of Srinagar was founded by the Mauryan emperor, Ashoka, and that Buddhism reached the Kashmir valley during this period. From there, Buddhism spread to several other adjoining regions including Central Asia, Tibet and China.

The dynasties

The kings of Kashmir described in the Rājatarangiṇī can be roughly grouped into dynasties as in the table below.

Notes in parentheses refer to a book and verse. Thus (IV.678) is Book IV verse 678.

| Gonanda I | The Rajatarangini (I.59) lists Gonanda I as the first king of Kashmir, a relative of Jarasasamdha of Magadh. |

| Lost and Unknown kings | Skipping over "lost kings" we come to Lava of an unknown family. After his family, Godhara of another family ruled (I.95). |

| Mauryas | The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive and powerful political and military empire in ancient India, founded by Chandragupta Maurya in Magadha, in 322 BCE. His grandson Ashoka the Great (273-232 BCE) built many stupas in Kashmir, and was succeeded by his son Jalauka. |

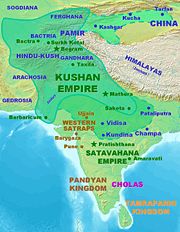

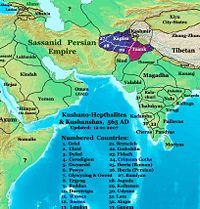

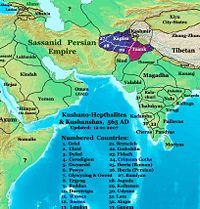

| Kushanas | After a Damodara ("of Asoka's kula or another"), we have Hushka, Jushka and Kanishka (127–147 CE) of the Bactrian Kushan Empire. (Note the confusion of dates in this and the following sections. Kalhana appears to made little attempt to determine the actual dates and sequence of rule of the kings and dynasties he recorded) |

| Gonandiya | After an Abhimanyu, we come to the main Gonandiya dynasty, founded by Gonanda III. He was (I.191) the first of his race. Nothing is known about his origin. His family ruled for many generations. |

| Some others | Eventually a Pratapaditya, a relative of Vikrmaditya (not the

Shakari) became king (II.6). After a couple of generations a Vijaya from

another family took the throne (II.62). His son Jayendra was followed by Sandhimat-Aryaraja (34 BCE-17 CE) who had the soul of Jayendra's minister Sandhimati. Kalhana says that Samdhimat Aryaraja used to spend “the most delightful Kashmir summer” in worshiping a lingam formed of snow/ice “in the regions above the forests” (II.138). This too appears to be a reference to the ice lingam at Amarnath. |

| Huna | Kalhana describes the rules of Toramana and Mihirakula (510-542 CE), but does not mention that these were Huna people: this is known from other sources. |

| Gonandiya again | After the Huna, Meghavahana of the Gonandiya family was brought back from Gandhara. His family ruled for a few generations. Meghavahana was a devout Buddhist and prohibited animal slaughter in his domain. |

| Karkota dynasty (625-1003 CE) | Gonandiya Baladitya made his officer in charge of fodder, Durlabhavardhana (III.489) his son-in-law because he was handsome. Lalitaditya Muktapida (724-760 CE) of this dynasty created an empire based on Kashmir and covering most of North western India and Central Asia. (With his account of the Karkota dynasty, relatively recent at the time he wrote his chronicles, Kalhana's information becomes more consistent with other sources.) Kalhana relates that Laliditya Muktapida invaded the tribes of the north and after defeating the Kambojas, he immediately faced the Tusharas. The Tusharas did not give a fight but fled to the mountain ranges leaving their horses in the battle field. Then Lalitaditiya meets the Bhauttas in Baltistan in western Tibet north of Kashmir, then the Dardas in Karakoram/Himalaya, the Valukambudhi and then he encounters Strirajya, the Uttarakurus and the Pragjyotisha respectively (IV.165-175). |

| Utpala | In the Karkota family, Lalitapida had a concubine, a daughter of a Kalyapala (IV.678). Her son was Chippatajayapida. The young Chippatajayapida was advised by his maternal uncle Utpalaka or Utpala (IV.679). Eventually the Karkota dynasty ended and a grandson of Utpala became king. |

| Kutumbi | After the Utpala dynasty, a Yashaskara became king (V.469). He was a

great-grandson of a Viradeva, a Kutumbi (V.469). Here maybe Kutumbi =

kunabi (as in kurmis of UP and Kunbi of Gujarat/Maharastra). He was the son of a treasurer of Karkota Shamkaravarman. Kalhana describes Shamkaravarman (883–902) thus (Stein's trans.): "This [king], who did not speak the language of the gods but used vulgar speech fit for drunkards, showed that he was descended from a family of spirit-distillers". This refers to the fact that the power had passed to the brothers of a queen, who was born in a family of spirit-distillers. |

| Divira | After a young son of Yashaskara, Pravaragupta, a Divira (clerk), became king. His son Kshemagupta married Didda, daughter of Simharaja of Lohara. After ruling indirectly and directly, Didda (980-1003 CE) placed Samgramaraja, son of her brother on the throne, starting the Lohara dynasty. |

| Lohara | The Lohara family was founded by a Nara of Darvabhisara (IV.712). He was a vyavahari (perhaps merchant) who along with others who owned villages like him had set up little kingdoms during the last days of Karkotas. The Loharas ruled for many generations. The author Kalhana was a son of a minister of Harsha of this family. |

Evaluation

Kalhana lived in a time of political turmoil in Kashmir, at that time a brilliant center of civilization in a sea of barbarism. Kalhana was an educated and sophisticated Brahmin, well-connected in the highest political circles. His writing is full of literary devices and allusions, concealed by his unique and elegant style. Kalhana was a poet. The Rajataringini is a Sanskrit account of the various monarchies of Kashmir, prior to the advent of Islam. Like the Shahnameh is to Persia, the Rajataringini is to Kashmir.

Translations

Rajatarangini was translated into Persian by Zain-ul-Abidin order.

There are four English translations of Rājatarangiṇī, by:

- Ranjit Sitaram Pandit

- Horace Hayman Wilson, secretary of The Asiatic Society of Bengal in the early 19th century, and the first English translator of the Rajataragini

- Jogesh Chandra Dutt in the late 19th century

- M. Aurel Stein, done in the early 20th century, in 3 volumes - the most comprehensive.pt.Gopikrishna Shastri (Ujjain) also tranlated in hindi.

http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/discussion/Rajatarangini

No comments:

Post a Comment